Introduction

The Greater Mexico City Area is the 15th largest urban economy in the world. Though the image of the periphery as place of shanty towns persist these are actually a very rare sight on the edge of the city. The poverty there is is not visible in terms of homeless people or undernourished children. Rather it is reflected in a lack of security when faced with sudden emergencies and very long working days. It is worth noting that the two most important contributors to the Greater Mexico City Area’s GDP, manufacturing and financial services both have strong presences on the edge of the city, the former in north of the city and the latter in Santa Fé.

Grocery stores

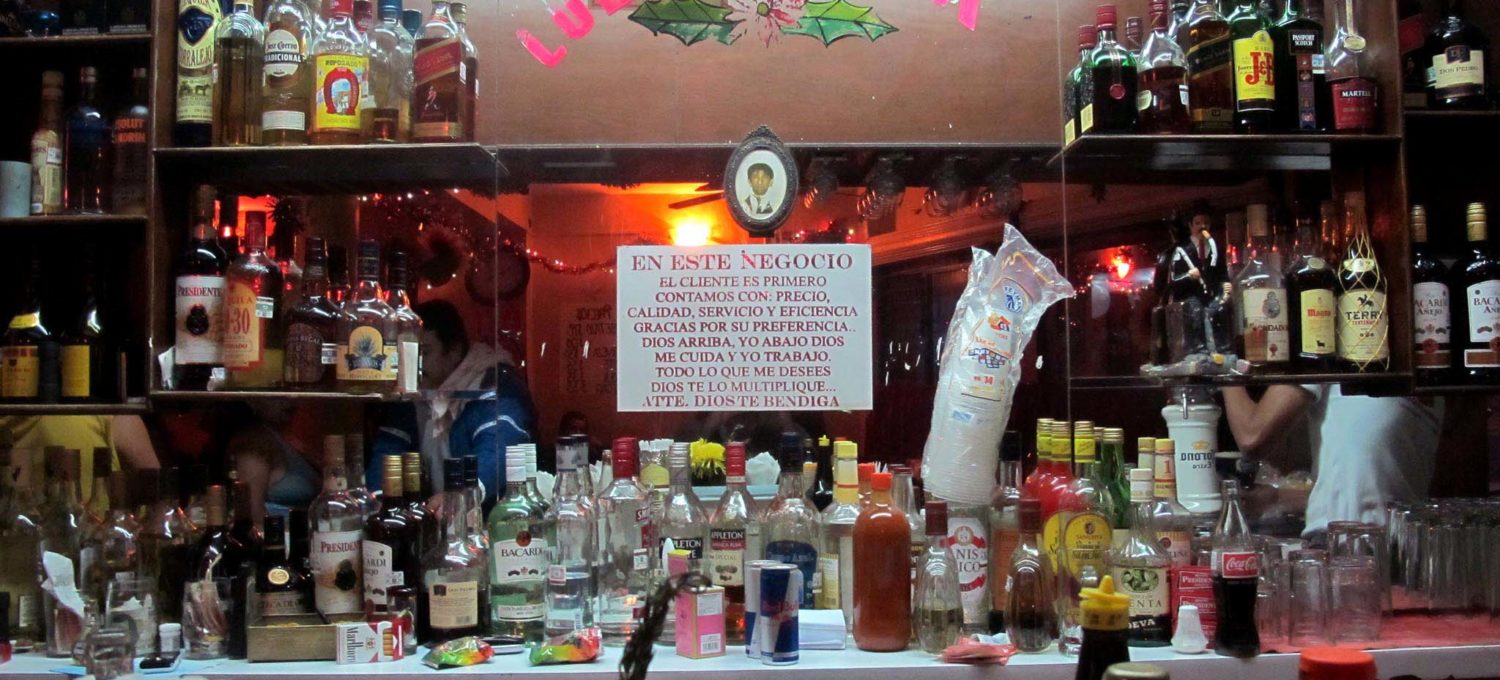

Among the first shops to pop up on the periphery are small grocery stores, selling cigarettes and non-perishable processed food products, such as soft drinks and packaged pastry products. In fact in many residential parts of the periphery they are the only kind of shop one will find. The basic logic of such shops is that some things are not worth travelling for. You don’t want to get in a bus to buy some candy or cigarettes or beer. So there is always demand in a residential neighborhood for such products as long as the shop is close by. Since growth on the edge of the city is primarily driven by residential colonization and often poor, the grocery store is omnipresent.

In general such shops make little money, perhaps between 3000 and 5000 pesos a month. Because the companies selling such goods have trucks with intricate routes and highly refined logistic operations it is very easy to open such a shop. The companies will provide refrigerators for cold drinks. And sometimes the companies will even leave the goods on consignment leaving a case of soft drinks in the morning and picking up the money from the sales in the evening on the way back.

According to government statistics about 1 million people work in the Greater Mexico City Area’s small grocery stores. Even on a worldwide level the corner grocery store in Mexico is an exceptional phenomenon. Nowhere in the world does Coca Cola for example need to make so many stops to deliver very small quantities of product. The same holds for the bakery products of Grupo Bimbo, the potato chips of Sabritas. Together they form the backbone of the small grocery store. The market supremacy of these brands relies in part on the inability of competitors to match their prowess in accessing these tiny points of distribution.

These shops could almost be seen as a kind of unemployment insurance, a minimum income easily accessible to anybody with a window looking out on the street. On the other hand the shops precisely because they are so easy to maintain do not contribute much to the human development of the city. Unlike more specialized forms of commerce in which people learn about new products and gain a more sophisticated understanding of a certain kind of product and salesmanship the grocery store gives people a small income and a refrigerator and little else.

Malls

When an area on the edge of the city is initially colonized the greater part of people’s income goes into building of houses. The areas are still poor, not everybody has a car and so the economy doesn’t have enough force to support a shopping mall. But inevitably as people age and gain more professional experience and the basic components of houses are finally built up the economy consolidates. This is the optimal moment for shopping centers to enter into the market, generally dealing a heavy blow to small shops which had sprung up locally to service more out-of-the-way neighborhoods on the edge of the city.

In this way money which once remained in the neighborhood in a local economy is now vacuumed out of the periphery to a more central destinations. The malls themselves are islands, isolated from the surrounding neighborhoods by fences and vast parking lots. There is therefore little economic spill-over from the malls into the surrounding neighborhood, except for the jobs they provide.

Most of the malls on the periphery there fore cater to basic shopping needs, clothes, food, appliances and a cinema. Some malls have started to include entertainment and recreational facilities, a sports bar, a videogame center for children, sometimes even a bar with a venue for concerts en route to becoming increasingly self-contained.

The malls of Mexico City also play an important role as the entry route for global brands and products into Mexico. The most natural place for a global brand seeking to enter the Mexican market is to open a shop in one of Mexico City’s 185 shopping centers. In this sense shopping centers are also portals of global commercial culture into the city.

Rural Production – Milpa Alta

Perhaps the principle difference between the countryside and the city is that goods from the fields outside of the city do not go directly into the city. Agricultural produce from different farms is first consolidated in rural centers and afterwards moves through the established national distribution system into Mexico and other cities. On the other hand there is a definite advantage to being on the edge of a market of 20 million people, especially for niche products for which freshness is a competitive advantage.

One part along the city’s edge with such a specialization is Milpa Alta where more than half of Mexico’s nopal (official figures estimate about 70%) is produced on terraced fields built into the hills. The leaves of the nopal are commercially particularly attractive as a product because they can be harvested throughout the year. In the morning the leaves are cut, in the afternoon they can be all brought together in the collection center in Milpa Alta and from there it can go to the different wholesale markets throughout the country, including the country’s biggest wholesale market, the Central de Abastos in Iztapalapa.

One producer estimated that he made around 10,000 pesos a month through the sale of his nopal. Agricultural production is hard work involving early rising and strict schedules. But one owns the land and the means of production leading to an aura of self-reliance and financial independence.

Another part of Mexico City’s agricultural edge making use of this competitive advantage is Xochimilco especially in the niche of fresh flowers. It is also notable that direct access to a large market gives suppliers more control over their logistics compared to villages lost in the mountains who are highly dependent on logistics suppliers.

Distribution centers

The first principle of logistics is to bring things together, move them together as far as possible and then ship them to their respective destinations. In the case of a city with 20 million people it is therefore useful for a large company such as Walmart or Coca Cola to have a distribution center near the city.

One example is the distribution center of Walmart in Chalco. The center supplies Bodega Aurrera supermarkets in the Greater Mexico City Area and is located just outside of the city under the hill of Cocotitlan on the freeway to Amecameca. A white square block in the landscape under the volcanoes it sends trucks out full of merchandise into the city, in the city the trucks are loaded at the distribution centers of providers and return loaded to Chalco.

Though the truckers themselves may contribute to the economy of local highway restaurants the distribution centers seem to have relatively little impact on the local economy around them.

Because distribution centers generate large amounts of traffic it is convenient that they are outside the city. Even the great wholesale market the Central de Abastos in Iztapalapa was on the edge of the city when it was inaugurated in 1982. Only shortly afterward was it swallowed by the city and now it generates traffic in the heart of Mexico City’s most populous delegation, Iztapalapa.

Factories

Factories tend to be built on or outside of the city to avoid congestion and pollution in the city. A notable phenomenon in the periphery is how these factories become geographic reference points and public transport nodes. Because they rely on workers getting there they are usually built closer to the built areas of the city since other wise transport to the factory becomes a problem.

An example of a factory as geographical reference point is the Ford Plant in Cuautitlan on the highway from Mexico City to Queretaro which employs around 800 people. Inside cars are assembled by robots in sleek, futuristic, assembly lines. Colored lines on the floor indicate the directions of production processes and workers where uniforms, hard hats and glasses.

Most of the city’s industry is concentrated on the highways to Pachuca and Queretaro leading finally to the United States and important source of imports and destination for exports. As factories are swallowed by the city they create long swathes of blocky square buildings along the highways, with behind them residential neighborhoods.

About 20% of the Greater Mexico City’s GDP comes from manufacturing, much of it along these two corridors which have impelled growth in the north of the city.